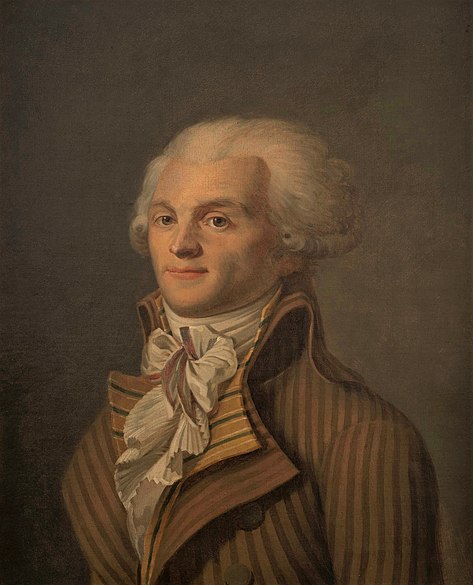

Maximilien Robespierre, called The Incorruptible, was the main figure of the Jacobins and has gone down in history as the personification of the Reign of Terror. His name has always been linked to the period of extraordinary measures which included executions by guillotine of the suspected counter-revolutionaries. He was presented as a bloodthisrty dictator, responsible for uncountable atrocities. This image dates back to the Thermidorian Reaction: those who deposed the Jacobins and presented themselves as moderates and claiming for order spread a very negative vision of the Jacobins and found the perfect scapegoat in Robespierre. The winners of the French Revolution, the respectable bourgeois who got the rights they were looking for, used the Jacobin period as a threat and a symbol of chaos and injustice. But what part of this is true? Who was Robespierre and what were his main ideas?

Robespierre was born in Arras, in North Western France. His family belonged to the low bourgeoisie: his father was a lawyer and his maternal grandfather owned a brewery. When he was 11 years old, he received a grant to study in Paris, where he became a lawyer too. Back in Arras, he started working and soon became very popular, because he participated in some very famous trials, defending workers against the abuses of the privileged. He also used the trials to criticize injustice and the bad running of the structures of the Ancien Régime. When Louis XVI called the Estates General in 1788 Robespierre wrote the book of grievances of Arras shoemakers´ guild and was elected deputy of the Third Estate. Once in Versailles, he joined the Club Bréton and later the Jacobin Club in Paris. In the National Constituent Assembly and also in the Jacobin Club he participated in a lot of debates, where he exposed his ideas and expectations:

- He opposed to the death penalty and explained that forgiving a hundred guilty people was preferable to sacrificing one innocent person.

- He defended the abolition of slavery and equal rights fot the inhabitants of the colonies

- He defended the participation of women in political clubs

- He supported universal suffrage, was against the division into active and passive citizens and believed in democracy

- He fought for the equality of rights for Jews and Protestants, defended religious tolerance and clerical marriage. He believed in God and thought that the decisions against the Church (like dechristianization) could be very negative to the Revolution. In fact, during the Jacobin Convention, he rejected the cult of Reason and proposed the alternative cult of the Supreme Being, as a way of reconciling religious beliefs with the revolutionary ideas.

- He was against press censorship and martial law and defended freedom of speech, freedom of press, protection of communications and freedom of association for workers.

- He considered that the right to survive was above other rights and was against punishing people who had committed crimes due to famine or because they wanted to live better.

- He considered that people were good by nature, defended social justice, education and the fight for improving the living conditions of the poorest.

- He was against wars of conquest and considered that the only wars worth fighting were the ones against tyrants, not against other peoples.

- His definition of nation included all the people who had expressed their will of living together under common laws, no matter where they were born.

Could a person with these ideas be considered the monster most books of history have depicted? Why did he change his mind about some of his principles? The answer can be found in circumstances. Many revolutionaries had to make important decisions when they were confronted with the dilemma of defending the achievements of the revolution and going on with changes or surrendering to counter-revolution. There were two opposed alternatives and they had to decide which one they preferred and what sacrifices were worth being done.

Robespierre was not obsessed with the idea of founding a Republic, because he was aware of the risk of eliminating monarchy, but when Louis XVI tried to flee from France and his conspiracy against the Revolution was discovered, Robespierre supported the supression of the monarchy and the execution of the king (he said "It is with regret that I pronounce the fatal truth. The king must die so that the country can live"). He became one of the most important figures of the National Convention and when the Jacobins took the control, he was elected member of the Committee of Public Safety. His responsibility in the extraordinary measures the Committee took was shared with the other members of this organ. He detested violence, but also knew that revolutions had always been violent. Violence was very present in the 18th century and the urgency of the situation in France demanded quick and extraordinary actions. Deciding against his principles had an extraordinary cost to Robespierre´s health and during the last month of his life he was constantly sick and felt very weak, but the responsibilty of building a new and fairer society made him come back to the Convention. A conservative reaction against the policy the Jacobins were following deposed them and on the 28th July 1794 he was executed by guillotine without previous trial, together with other Jacobin leaders. The memory of their efforts was hidden by the bloody stories the winners told about them. They invented the expression Reign of Terror to define the Jacobin period and spread the ideas everybody links to Robespierre. But the Jacobin Convention and especially the Incorruptible deserve a fairer study.

Here you have one paragraph of one of Robespierre´s most important speeches, on political morality:

In our land we want to substitute morality for egotism, integrity for formal codes of honor, principles for customs, a sense of duty for one of mere propriety, the rule of reason for the tyranny of fashion, scorn of vice for scorn of the unlucky; self-respect for insolence, grandeur of soul for vanity, love of glory for the love of money, good people in place of good society. We wish to substitute merit for intrigue, genius for wit, truth for glamor, the charm of happiness for sensuous boredom, the greatness of man for the pettiness of the great, a people who are magnanimous, powerful, and happy, in place of a kindly, frivolous, and miserable people—which is to say all the virtues and all the miracles of the republic in place of all the vices of the monarchy. . . .

On Political Morality, 5th February 1794

Satirical drawing of Robespierre executing the executioner after having guillotined everyone in France

Most of the content of this post comes from two books in Spanish I´ve read recently:

- McPHEE, Peter, Robespierre: una vida revolucionaria, Ed. Península, Barcelona 2012. This is an extraordinary and documented biography, written by an Australian historian. Here you have some links about this book in English and Spanish:

- GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ, Javier, Robespierre, Galaxia Gutenberg, Círculo de Lectores, Barcelona, 2012. This is a very long historical novel (more than 1,000 pages) that I still haven´t finished, but it has a very interesting post scriptum about how historians have treated Robespierre and the Jacobins and the reasons for this bad treatment. Here you have a review of this novel in Spanish:

And finally, here you have some Robespierre´s quotes:

- The secret of freedom lies in educating people, whereas the secret of tyranny is in keeping them ignorant.

- To punish the opressors of humanity is clemency; to forgive them is cruelty.

- Any law which violates the inalienable rights of man is essentially unjust; it is not a law at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment